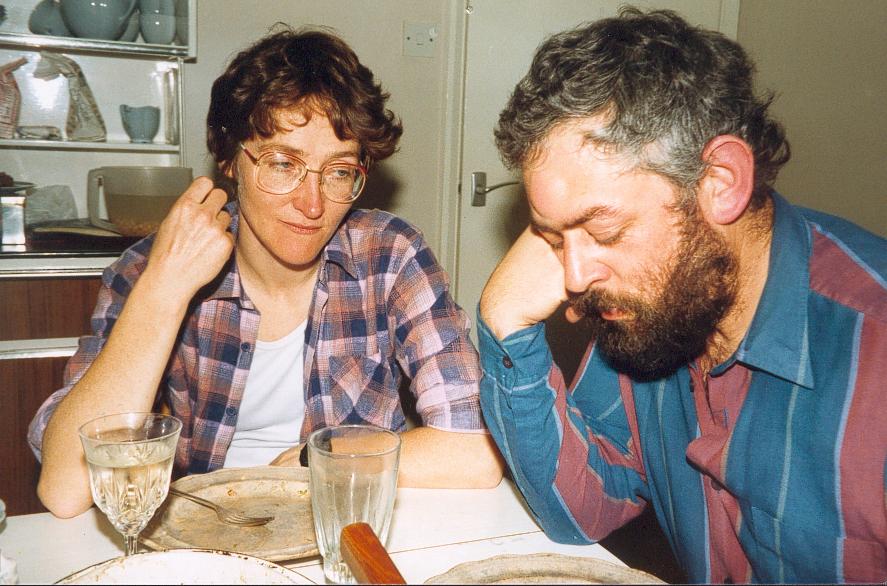

Rachel and Lucifer

Rachel and Lucifer

Rachel

I want to record and celebrate

First: the physical person of

Rachel - her body:

Rachel running, Rachel cooking, Rachel with her cat Lucifer

Rachel the lover, Rachel the walker, Rachel the climber who, at

her best, climbed with a fluidity and elegance that I

envied.

Not in opposition to her cerebral side - her formidable

intelligence, her knowledge of political and economic theory, her

vision of how the world ought to be - because Rachel had

deconstructed those oppositions of theory and practice, of mind

and body

Perhaps most clearly expressed in our

slogan from the 70s - ‘the personal is the political’

- itself a deconstruction of the conventional opposition of these

two terms: a refusal to accept them as the unavoidable

defining structure of political life, a recognition that

the privileging of the political over the personal must be

challenged

she always said she didn’t understand postmodernism, but she

was, appropriately, living it, because of the failure of

modernity to give us what we need and what we desire, and the

irresistible drive to supercede it.

And so I come to the second thing I want to record and celebrate here, without, I think, any inconsistency: I move on to something closely and intimately related, which I’ll call the future of work: economic development, and specifically, because of my time with Rachel, workers’ co-operatives.

I met Rachel in 1976 when I joined a group setting up the Balham Food & Book Co-op. We worked together in it, and became lovers and partners - a partnership which lasted until recently, and which now was replaced by a friendship which we were both looking forward to developing.

Working at the Balham Food & Book Co-op was exciting, stimulating, always hard and at times appalling and disastrous. It was, along with the areas of economic development work to which we later moved (Rachel at the Greater London Council), for us, a working out - at least a beginning of working out - how work in the future could and should be in practice, a prefiguration of the changes to a better world that we desired, the theory of our desires tested in practice. The theory, and the desire, guided our practice and were also the result of it.

For Rachel especially, that work never stopped, it seems to me. I’m sure she was able to achieve all she did at the GLC and then at Kirklees, and then become, at Barnsley, the kind of boss who exercised her skills to enable people to develop and give their best - she achieved all this partly because of what we worked through at Balham and, of course, through her intense practicality, her personal awareness that putting beans in bags and caring for your co-workers was at least as important as negotiating the next loan.

But what reminded me of this - told me that I must speak of this here, today - was seeing the Socialist Choir at their practice last week, watching them working together, helping each other, working co-operatively, supporting and caring for each other in the practical business of getting the songs right - I saw more clearly than ever why she was so much at home in the choir, because she had never stopped doing what we started together in that house - a housing co-operative of course - in Wandsworth.

But now: the hard part

Because the physical body of Rachel was in no way separated from everything else about her

her body - there - lifeless - fills me with both grief and terror

terror because I now know not only of her death but of my own: that’s how we can all end, suddenly, in a moment, without warning

and I see, again and again, her body on the rocks: Rachel no longer able to do all she was in process of doing

and I can only hope to work through my

grief and to dispel my terror

by continuing to live and work in accordance with how she lived

and worked

in comradeship with all the rest of you who are here, in body or spirit

- Andrew

Ruth and Rachel in Wadi

Rum, Jordan

Ruth and Rachel in Wadi

Rum, Jordan

Rachel and Andrew